Zephyr “Zed” Wildwood had been a manager at the grocery store on Broadway for nearly six years. While he was initially hired to stock shelves, that hadn’t lasted long. The O’Sullivan heirs had promoted him out of the back when it became apparent that Zed could talk much faster than he would walk. He donned a new uniform and grinned a half-wide grin to see his name on a placard at the front of the establishment.

This was what he deserved.

He took to the position like a duck to water, easily matching name to face and able to quickly regurgitate seemingly extraneous details about the lives of his customers. All the regulars came to know Zed, happy he always had an answer to their inquiries, no matter how inane the question.

Through the compliments and flattery, few cared whether he was right or wrong.

The brother and sister who owned the store, having taken over after the death of their father, were content to finally have a man in charge who could take care of himself, not to mention refrain from bothering them about the trivialities. Zed seemed perfectly suited to the job, and his numbers always lined up. Sometimes the old Newburghers stopped the O’Sullivans on the street and remarked on how well-run the store had become.

Just like the good old days.

The O’Sullivans celebrated their livelihood. The store was practically running itself, and they merrily cashed the checks. They figured Zed was a natural people-person, and they weren’t wrong; with his gift for gab he could schmooze the socks off an eel.

When Cedric came back to Sullivan’s like clockwork the following afternoon, Zed took to him immediately. The whole picture was more than he could have asked for. The boy had bright eyes and a charming demeanor and it was all-too-obvious that he wasn’t from around here. Not at all. Zed smiled slyly to hear him call the stuff “pop” and knew he’d found a sucker.

And better than that, Zed gleaned, he was desperate for work. With a little elbow grease, he just might do anything.

Sure, he had the kid fill out a W-4 and write out his references and phone numbers and all that. Said he could start next week if everything came back okay.

And it would come back okay.

When Zed offered to cash the paychecks “for his convenience”, Cedric went along with it, none the wiser. Perhaps he should have been suspicious. Perhaps he should have thought twice. But when the man with the cards in his hand walked right by the skeleton in the closet, Cedric kept moving forward. He had no idea that his signature was doomed for a dead-end in a dusty manila folder, never again to see the light of day.

Zed took the sign out of the window, satisfied with his good fortune, and the summer went on, week after humid week. He had Cedric run the register, figuring the corn-fed kid wasn’t likely to pocket the spare change. Zed was beaming; his new employee was eager to work nights and weekends, always showed up on time, and looked rather tidy in his navy smock.

Yes, he looked really rather… Nice.

He’d made a valuable acquisition, and Zed was pleased with himself, thinking it just one more thing the world owed him.

And there were a lot of things the world owed him.

The days began to wear thin, and sometimes the nights were cold when the wind swept a course over the river. Zed thought there were still profits to be made. He knew the way of things. People’s habits changed with the seasons. They dried out their swimsuits and put their sweaters on hangers. They called up old friends and organized dinner parties. They bought chickens and gravies and mused about the proper way to stuff a bird.

Zed was not one to leave money on the table.

Cedric heard Betty shuffling in the living room as he came down the stairs, dressed for work.

“Morning,” he said, stepping in to greet her. She had a square album sleeve in each hand. “What’re you listening to?”

Betty held them out, pressing him to come over and have a look.

“I was trying to pick between these two. Some favorites of mine. What do you think?” Whether it was how to best cook an egg or whether people should be allowed to curse on television, Betty had a strong opinion about everything.

Cedric eyed both albums, completely unacquainted with the selections, and pointed to the one done in the blueish fuchsia of daybreak. A woman’s forlorn face adorned the fading color, melancholy in her tired gaze.

“She looks so—” he tried to find a ten-cent word, but settled on the first five-cent thing that came to mind. “Sad.”

Betty placed the other record down on the pile next to the turntable, then looked toward her tenant. “Lady Day had a lot to be sad about. She lived a hard life. The world wasn’t kind to her, not when she was young, and not when she got famous.”

Cedric looked at her and said nothing.

“Maybe things would be better today, but I’m not so sure. The world was different then; rules and expectations were harsh, but maybe it isn’t any different now either.”

She took out the disc, aligned it on the center of the player, and set the needle to play. The metal scratched for a moment and then filled the room with the woman’s rich voice.

“The first song was new at the time,” Betty began, speaking just loud enough to be heard as Cedric stepped closer. “But most of the rest were re-recordings of her original hits. Famous long before you had the Billboard.”

Cedric let the music wash over him, feeling all-at-once transported to another time and place. He was struck by how truly the voice formed the holy centerpiece of the experience, letting the rest of the instruments play subtle as backdrop. The two stood silent for several minutes as the vinyl spun around and before he knew it, the first song finished and another story began.

“It’s—” he looked down at the player, remembering the cassette player in his pocket. The pieces emanating from the record were short, shorter than he was used to, and he felt they were over nearly as soon as they’d begun. “Not bad.”

“’Not bad’?!” Betty laughed, incredulous. “Damn me with faint praise!”

Betty lifted the needle and moved it forward, so that it started playing in the middle of another song. She must have known exactly where to place it. “Listen to this next one. Tell me it’s not bad.”

They watched the needle bob up and down as the sunlight streamed in through the window. No longer in the realm of a lovelorn teenager, Cedric’s breath slowed as Holiday painted a very different picture before his eyes. Betty spoke without looking at him.

“This one’s called Strange Fruit,” she said, lowering her voice. “Song got her in trouble with the government. They didn’t want her singing it. Said it was—”

She paused, and then spoke with sudden scorn. “Un-American.”

Cedric listened quietly as Holiday continued to sing; beautiful, emotive, haunting.

“I saw her once. Small club uptown called the Blue Note.”

He looked up at her, but she was gazing toward the window.

“I was just a pretty young thing then. Little white girl from Newburgh, alone on the train to Harlem; can you imagine? My parents would have locked me in my room and thrown away the key.” Betty might have been suppressing a grin. “I think I told them I was studying for an exam.”

“She was incredible. Changed my life. She was fierce and fragile all at the same time. Gardenia in her hair, just like all the pictures. Voice like velvet.”

Cedric looked down at the record player. “Did she… sing this?”

Betty paused for a moment.

“No,” she replied, taking a somber tone. “Don’t think she could at this point. No one would let her. Not anymore.”

The words soon stopped, and Betty lifted the needle, leaving the small room in silence.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same,” she continued. “Every generation thinks they invented rebellion. But this has been going on since the world was new.”

The break room in the back of Sullivan’s Market smelled heavily of cigarette smoke. Sometimes, when one of the employees would take their TV dinner out of the freezer and give it a zap, the husky smell of Salisbury steak or macaroni and cheese would fill the air. But without the respite of an open window, it would only take a few ticks of time before the place again reeked of the grey ash and discarded filters at the center of the Formica.

When Cedric was off-the-clock, he came here and sat with his eyes closed in the dim light. With some of the first returns in his pocket, he’d purchased an off-brand Walkman and liberated his collection of tapes from languishing in an old shoe box. This became his daily habit. He’d make nice if someone entered the room, but as soon as they’d leave, he’d turn his eyes to the minute hand and calculate how long he had left before he was required to return to the front. Maybe he’d make it to side B, or maybe he’d start there instead, a little change of pace. But they always seemed to interrupt him at the best part.

Today was no different.

“Hey, Kenyon. How’s it hanging?”

Cedric pressed pause on his cassette player and removed the headphones from his ears, letting them dangle as a torc about his neck.

He looked at Zed. “Nothing much. Do you need me?”

“No, no, nothing like that,” Zed replied. “It’s quiet today. Enjoy your break.”

Cedric watched as the man, tall and lanky, topped with a tangle of medium-brown hair, opened the door to the fridge and bent down to investigate what had been left inside.

“No one buys vegetables so they’re going bad, tomorrow’s shipment’s gonna be half what we need; the usual shit.”

Head still immersed in the cold air, he spoke to Cedric while twisting his neck to the side.

“Just wondering if you’re doing anything tonight.” Zed shoved the door shut and the compressor started with a spasm.

Cedric unconsciously tightened his grip on the Walkman. Usually, if he worked the early shift, he would sit in the library until it closed. The air conditioning was a welcome comfort in the uncertain early autumn. But if he responded to this summons, that wouldn’t be an option. He wasn’t particularly fond of disturbing the habits he’d developed over the past few months. And he wasn’t particularly fond of Zed.

But sometimes, he thought he was lonely. Other times, he thought he enjoyed the silence. But abject refusal was not something he’d yet practiced much.

“No, not really,” he admitted.

“Right on,” Zed replied, shifting his weight over his feet. “Come over to my place and hang out for a bit. Meet my girl. She’s a great cook.”

The other cashier came on the loudspeaker and summoned the manager to the front of the store. Zed uttered a grunt of irritation and made his way toward the door of the breakroom.

But he was not done talking.

“Cool, we’re on. See you in a few.”

Zed’s apartment was not far from Sullivan’s. At the conclusion of their shift, with no one else in the store, Cedric left out the back and followed his boss, glancing from side to side in the near moonlight. By the time Zed had finished his cigarette, the two arrived at a narrow brick house that shared its walls with a whole row of other narrow brick houses. These kind of homes were common in this area of Newburgh, and their close proximity allowed the denizens easy access to downtown. For those whose circumstance precluded them from a mortgage, these buildings filled the gap.

One key on the ring opened the front door, and another opened his private sanctuary. Zed lived on the first floor.

“It’s not glamorous, but it’s home,” he prefaced as the metal door creaked open, seeming downright impersonal in its attempt at ultimate security. “I think Gloria’s making chicken. You like chicken?”

But Cedric knew it was more a statement than a question.

As he entered the trim abode, the first thing he noticed was an enormous piece of exotic glassware towering nearly two feet tall atop a coffee table.

Cedric was reminded of an Erlenmeyer flask.

Inside the reservoir were several inches of murky water, into which a narrow stem was submerged. A gradient of chunky residue rose on the inside of its neck. Looking at the strange thing, Cedric heard Zed engage the deadbolt on the door.

Just beyond the table lay a black leather couch and, to the other side, presumably the intended focal-point of the room, a colossal flat-screen television.

“What do you think? Ain’t she a beaut?” He declared, stepping into the room and removing his apron. “Mitsubishi. Fifty inches. You ever seen anything like it?”

Cedric surveyed his surroundings, cognizant of the fading blueish-green walls, rather bare with few hanging pictures. The carpet was dingy with the filth of ages. “It’s nice.”

A woman strode out of the kitchen cut several yards to the side.

“Hey Zed, who’s your friend?” She had dark blonde hair, long, framing a rather gaunt set of cheeks. Pretty, Cedric thought reflexively, or something like it, but she wore too much makeup and her cheeks shone like painted plastic.

“This is Cedric, my buddy from Sullivan’s. Good kid. Works hard.” Zed noisily flopped his keys upon a table in the entry and covered them with the crumpled apron.

“Nice to meet you, Cedric. You like chicken?”

Cedric was taking off his shoes. “Yeah, I eat chicken.”

“Come have a seat, Ced. Take a load off. What’s mine is yours.” Zed walked over and collapsed into the understuffed leather for a moment, watching his guest, and then sat forward with a sudden rush of energy.

He opened a drawer concealed beneath the surface of the table as Cedric settled down on the couch. He realized, watching silently, that Zed wore the same face at work that he did at home. That irrepressible energy wasn’t an affectation of the apron or the hat. He was always trying to sell something.

Zed removed a rectangular wooden box and a squat silver cylinder from the unseen drawer and placed them on the glass table. He opened the hinged lid of the box to remove several more items, including a red Bic.

“You want some of this?” He pulled a cluster of green buds from a Ziploc and loaded them into the grinder. “My guy got some good skunk this week. Primo homegrown.”

He reassembled the device and twisted the silver lid back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

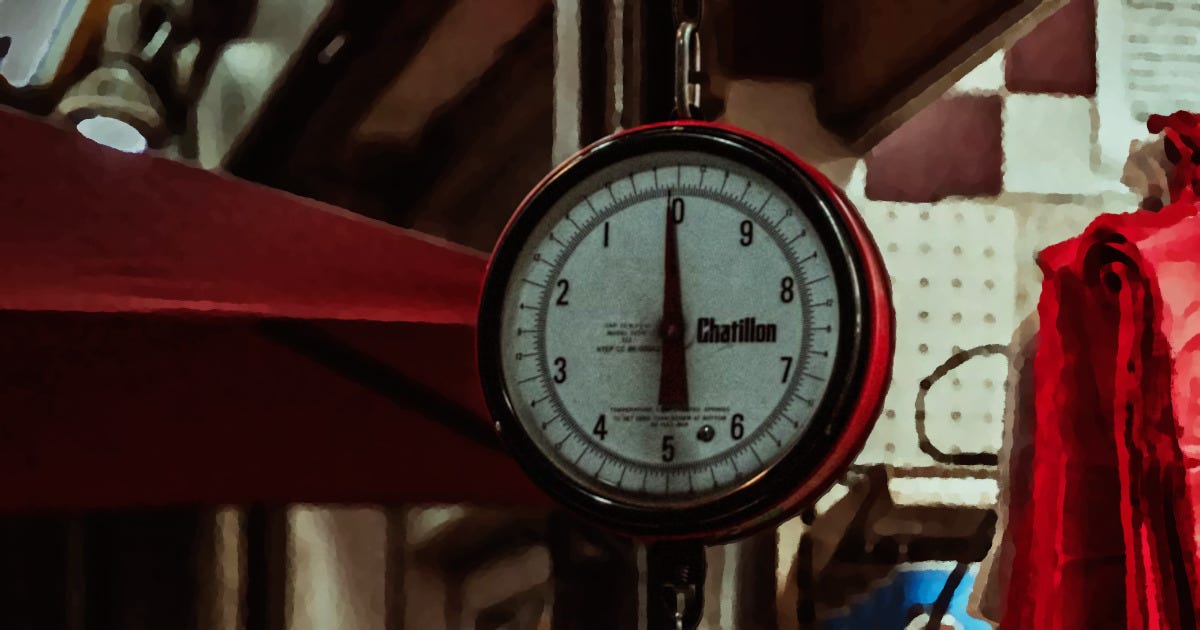

“Uh, I don’t usually…” Cedric watched as the man dumped the crushed flower on a small piece of folded notebook paper, took a pinch between his fingers, and loaded the bowl of the water pipe. Now done packing the hit, he gripped the neck to bring the thing over the edge of the table. It was huge, unwieldy, and impossible to hide.

Zed put his mouth to the opening of the tube, held the lighter to the green, and simultaneously started the fire while inhaling, sending the sound of bubbling water through the room. Cedric tried not to stare as the man brought the vapor into his lungs, moved the glass away from his mouth, and held himself still for several seconds, perhaps the only time Cedric had ever seen the man cease motion.

He soon relented and white smoke poured from his mouth, Zed’s voice somewhat muffled as the remaining exhaust dissolved into the air. “I know bong’s a little dirty; needs a cleaning, but she hits like a truck.”

Zed set the piece down on the table, the interaction between glass and glass almost loud enough to cause alarm. “Let me know if you change your mind. Don’t wanna be a Scrooge.”

He picked up a remote control from the arm of the couch and turned on the television. He flipped channels until he found The Simpsons. Cedric looked at the enormous screen, then back at the wisp of smoke rising from the exhausted bowl, and then to nothing in particular.

Zed’s girlfriend called from the other side of the apartment, “Dinner’s almost ready, boys!”

The two watched the yellow people loom over them, larger than life. Cedric had never seen such a gigantic television set, and certainly not in someone’s house. And at the volume Zed had set, he almost believed he was in a theater.

Except, of course, for a few key differences.

“You like cream corn, Cedric? Rice pilaf? It’s the San Francisco treat!” Gloria yelled from the kitchen.

Cans, boxes, jingles —

“Yeah, thanks, sounds good.”

Zed packed a second sticky payload into the blackened bowl while Cedric felt the pull of the blaring transmission.

“So where’d your mom get a name like ‘Cedric’, huh? Never heard of that one,” he said to the flick of the lighter.

Cedric could hear the flame sizzle as it set the tarry plant matter alight. His heart stuttered. “It’s… uh—”

“A character in a book.” He paused, and clarified. “Little Lor—”

Zed interrupted as soon as thought rose to his mind, coughing as the exhalation spread into the room. “Guess I don’t have much room to talk. My peacenik parents didn’t leave me with much better.”

“What kind of stupid-ass name is ‘Zephyr’?” He asked with derision. “Haven’t seen those fuckin’ phonies for a few years now. Good riddance. Assholes.”

The voices on the television kept droning on.

“Started having people call me ‘Zed’ when I was ten or eleven or whatever. I got the idea when we learned how to say the alphabet in French. You know any French?”

Cedric shrugged. “I took a few years.”

“I liked how they ended it,” Zed replied. With a broken affect, he recited the last three letters of the alphabet. “Eeks, Ee-grekk, Zed.”

“Zed.” He repeated. “Just kinda stuck with me.”

Gloria came out of the kitchen with two plates of food and set them before the men on the low table.

“Hell of a lot better than ‘Zephyr’.”

His girlfriend spoke rapidly to Cedric, ignoring Zed’s chosen topic. “I’ll get you a fork; hey, you’re cool, yeah? I made brownies last night, you want one? They’re alright. Not my best, but they’re alright. Double chocolate.”

Cedric didn’t quite know what to say. Zed interjected, abandoning his personal anecdote.

“Gloria makes good stuff. You know, you can’t just throw the leaf into the box mix and call it a day. That’s a rookie mistake. You gotta cook it in the butter. That’s how you do it. Coconut oil works too ‘cause you can drain it but Gloria says the butter tastes better.”

She smiled and did a little curtsey.

Zed continued to pontificate. “Of course you could use kief, but not everyone can foot that kind of—”

But Cedric was hardly listening. He thought back to what Zed had made of his name, and wondered if he’d made a terrible mistake. Wondered if no one would ever understand. Wondered if they’d always miss the point.

“Yeah, sure,” he stammered at the offer. “I’ll try one.”

Cedric sat there as Gloria brought him a utensil for the food. And as he ate dessert before the main course, he looked about himself in that blue room and wondered how much time needed to pass before he could leave and get the fuck out of here.

When he would finally leave and get himself outside on the darkened street, he’d start his cassette at the beginning, and maybe he’d get through one side before he got back to Betty’s house. Maybe both if he walked slowly. Soon, he’d be back in his room. Back to the quiet. Lock the door.

The TV continued to talk but the room was otherwise silent as they processed the meal.

Gloria, having chosen to eat alone in the kitchen, all but disappeared after their plates were cleared. Zed leaned back against the cushions and Cedric, now acclimated to the pungent odor, wondered when he was. As the boy ahead of him delivered one of his many catchphrases, Cedric was sure he felt nothing, nothing at all.

“Eat my shorts.”